Most people know very little about the actual factuals of the criminal justice system, getting their impression of policing from what they see on the TV.

A British Crime Survey found that only 6% of the public think the media gets it wrong. That means a whopping 94% trust what they see on mainstream media platforms.

So all kinds of – non-policed, unregulated – shows, dramas and even reality-style programs shape how we think about policing, often blurring the lines between fact and fiction.

The psychology of policing by TV is smart: by portraying police as heroic, competent and morally upright, television creates a comforting illusion of safety and order. And then it costs less to do any of the actual policing…

CAR CRASH TV

Today, complex police dramas are few and far between, giving way to cheaper to produce, high quantity, low grade “police infotainment” – CCTV footage and patrol car arrests packaged as quick, satisfying justice for the modern viewer.

It’s everywhere. It’s fast, simple, and leaves little appetite for question what’s really going on behind the scenes.

- 24 Hours in Police Custody: A documentary series that follows Bedfordshire Police as they respond to emergencies, investigate crimes, and arrest suspects

- Britain’s Most Evil Killers: A series that explores the crimes of some of Britain’s most brutal killers

- Policing Paradise: A series that follows a team of detectives policing the islands of Bermuda

The Thin Blurred Line: Reality Television and Policing

So it’s not entirely a stretch to say that the biggest police force in the world isn’t the NYPD, the Met, or even the PSNI.

It’s the TV.

With its endless crime dramas, reality shows, and news reports, TV effectively acts as a cost-effective arm of the state, shaping public perceptions of law and order without the need for an effective, functional police force that operates in the public interest.

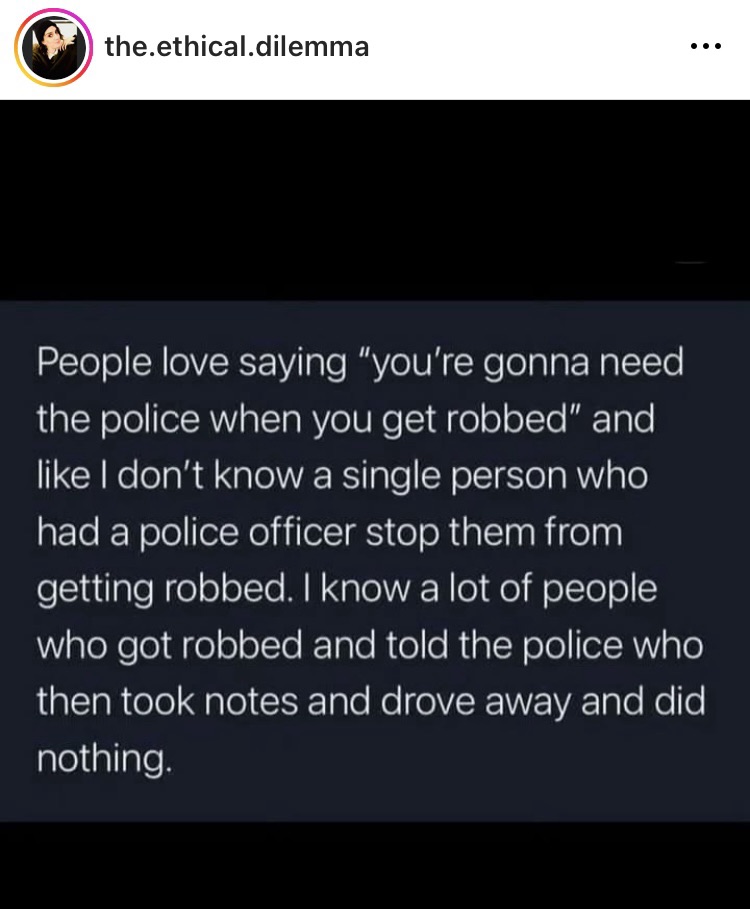

These programmes reinforce the idea that crime is constantly being solved and justice is always served, making it easier for governments to justify underfunded or mismanaged police forces.

So, instead of addressing systemic flaws or investing in meaningful reforms, this media-police partnership provides a cheaper, more palatable alternative to public accountability – one that entertains, pacifies, and ensures compliance without lifting a finger in the real world.

People stay law-abiding because TV convinces them the system is effective, efficient, and just. The constant portrayal of swift justice creates a fear of consequences while reinforcing trust in a system that often fails to match the fiction.

Defund the Police

Emerging in 2020, the Defund the Police movement advocates for narrowing the scope of police responsibilities and shifting many public safety functions to other entities better equipped to handle them.

This includes increased investments in mental health care, housing, community mediation and violence interruption programs.

The funniest thing about this? The people and institutions who are vocally vitriolic about it are also the people who have been “defunding” the police for years through budget cuts and pay reductions.

These budget cuts have had tangible impacts on policing capabilities. For instance, the Metropolitan Police Service faced a £450 million funding deficit, resulting in plans to reduce the number of officers by up to 2,300.

A study by the Institute for Fiscal Studies highlighted that police spending reductions have direct impacts on crime prevention, ultimately affecting crime reporting and citizens’ welfare.

Who all this IS good for are the private security firms needed to support traditional policing roles. Ker-ching!

Policing on a Budget

Keepers of the Peace

And in Ireland in April 2024, the head of the Garda Síochána Ombudsman Commission expressed major concerns over cuts to Garda community policing, highlighting negative impacts on public trust and community relations.

Despite promises in Budget 2025 to recruit 800 to 1,000 new Gardaí, the force continues to grapple with staffing shortages, leading to the disbandment of key units like the DMR North Burglary Response Unit, which had made over 600 arrests in two years.

The Garda Síochána – Guardians of the Peace – was established in 1922 following the formation of the Irish Free State with the will to make a deliberate break from the heavily militarised and divisive Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) – a tool of British colonial oppression.

Unlike its predecessor, the Gardaí were founded with the ethos of community policing, aiming to serve and protect the people rather than enforce a foreign power’s rule. Early Gardaí were unarmed to deliberately help foster trust and avoid the heavy-handed reputation associated with colonial policing.

However, as much as the Irish pride themselves on this more community-oriented ethos, there’s a case to be made that Ireland, as a nation, may be particularly ill-suited to running a ruthlessly effective police force.

The Irish temperament tends to value relationships, wit, and pragmatism over rigid authority or blind rule-following. Centuries of colonial oppression bred a natural scepticism of power and an inherent sympathy for the underdog. These cultural traits make it challenging to adopt the “us versus them” mentality required for the kind of policing seen in imperialist or authoritarian systems, which often prioritise enforcement over empathy.

The craic is that the very idea of doling out punishment with ruthless efficiency feels alien to a culture steeped in storytelling, humour, and an innate understanding of human fallibility.

But then you’ve got these guys…

The Garda Síochána and the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) share the island of Ireland but represent starkly different histories, ethos, and approaches to policing.

While the Gardaí emerged from the Irish Free State’s desire to create a policing body that prioritised community trust and non-militarisation, the PSNI evolved from a long history of sectarianism, enforcement, and heavy-handedness under British rule.

The PSNI: An Apparatus of an Apartheid State

In stark contrast, the PSNI – established in 2001 as a successor to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) – carries a legacy deeply intertwined with sectarianism and state-sponsored oppression.

The RUC was created in 1922 at the establishment of ‘Northern Ireland’, functioning as an overtly militarised force tasked with upholding the interests of a unionist, Protestant-dominated state.

For decades, the RUC effectively operated as an arm of the British government, suppressing Irish nationalist and republican communities with tactics that ranged from heavy surveillance to outright violence.

The force was overwhelmingly Protestant, reinforcing perceptions of bias and sectarianism.

During the Troubles, the RUC became infamous for its collusion with loyalist paramilitaries, allegations of torture, and its role in enforcing apartheid-like policies against the Catholic minority in the North.

Far from fostering trust, the RUC symbolised division and oppression, alienating large swathes of the population it was meant to serve.

Rebranding Without Reform

The creation of the PSNI was part of the Good Friday Agreement’s effort to reform policing and address these deep divides.

The name change from the RUC to the PSNI, as well as the introduction of measures like independent oversight and a commitment to recruiting more Catholics, was meant to signal a shift toward fairness and equality. Yet, the legacy of the RUC continues to cast a long shadow.

While progress has been made in diversifying the force, the PSNI still faces accusations of bias and systemic issues.

For many in nationalist and republican communities, the PSNI remains a tool of the British state rather than a neutral body working in the public interest. Its militarised history and its continued role in contentious events, like policing protests and parades, keep it tethered to its past.

Both forces face modern challenges: the Gardaí struggle with underfunding, staffing shortages, and operational inefficiencies, while the PSNI continues to grapple with sectarian divides, officer stress, and a lack of full trust from the communities it serves.

However, the contrast in their origins and ethos highlights how policing can either unify or divide, depending on whether the focus is on service or control.

Ultimately, the Garda Síochána stands as an example of what policing could aspire to be – flawed but community-focused – while the PSNI serves as a cautionary tale of what happens when policing becomes a tool of oppression and division.

I know which one I’d prefer.

To get back to the point: policing by TV is unarguably the most effective, cost-efficient enforcement mechanism ever devised.

Crime dramas, reality shows, and sensationalist news all work together to shape public perceptions of law enforcement as infallible, just, and necessary, instilling fear of crime and trust in authority.

It conditions us to have faith in a system that often fails in practice.

Leave a comment