https://www.irishcentral.com/news/thenorth/end-of-civil-rights-movement-prelude-bloody-sunday-and-aftermath

They say revenge is a dish best served cold. But in the case of fair employment in Northern Ireland, it was cooked slow, served stateside, and dished up with a side of Boston sass and Bronx grit.

Let’s talk about the MacBride Principles.

Let’s talk about how a ragtag mix of Irish-American lawyers, bartenders, senators, and exasperated pub philosophers managed to do something the British government had refused to do for decades: admit that Catholic workers in the North of Ireland were being shafted at every turn. And do something about it.

Let’s also talk about Noraid, Martin Galvin, and how the diaspora proved that home isn’t always a place on a map. Sometimes, it’s a memory you won’t let die.

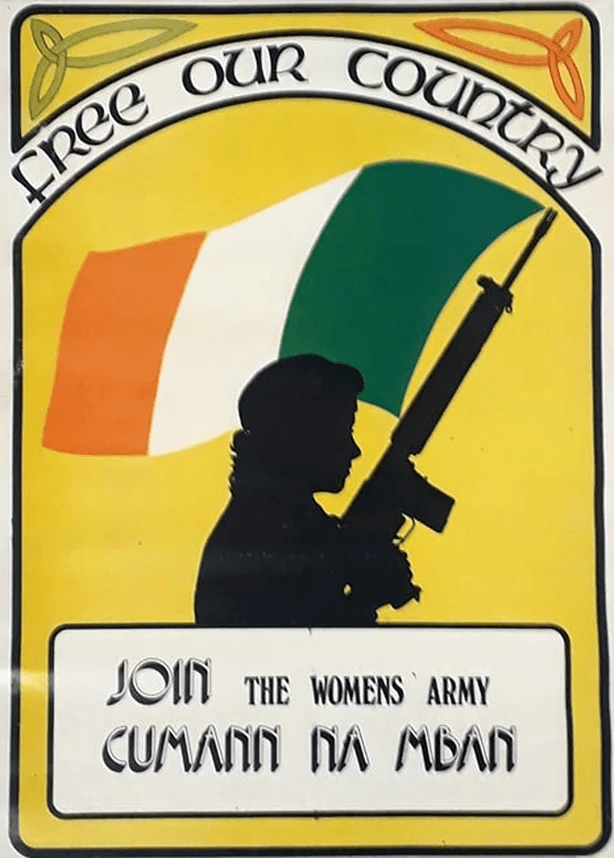

And while we’re at it – let’s not forget the women. Because when we talk about oppression in the North of Ireland, and we don’t talk about how it landed on Catholic women’s backs like a second shift – we’re missing half the picture.

The Corporate Front Line of the Troubles

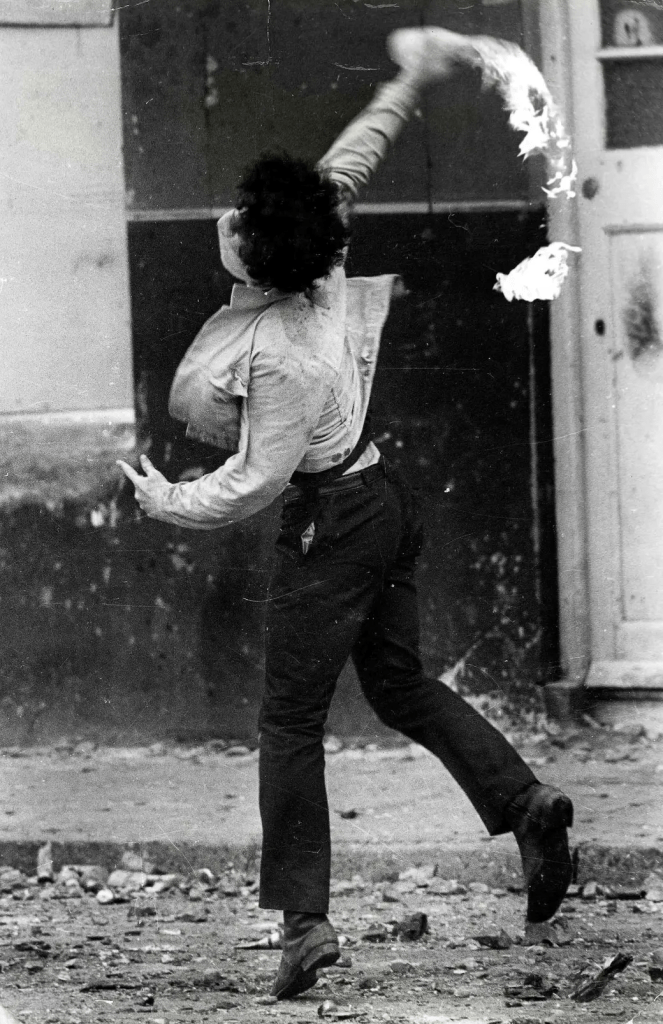

Northern Ireland in the ‘70s and ‘80s was a cauldron. The Troubles weren’t just fought on the streets of Belfast and Derry with bricks, bullets, and prayers. They were fought in boardrooms too – in who got hired, who got promoted, and who got turned away at the factory gates.

Catholics were on the losing end of that economic war. And Catholic women? They weren’t even considered combatants.

They were undereducated by design, expected to hold the line at home, clean the streets as part-timers, or do the unpaid labour of community peacebuilding while being paid in holy water and martyrdom.

To be poor, female and Catholic in Northern Ireland wasn’t just a social disadvantage. It was a life sentence.

So when the diaspora rose up and started demanding change, it wasn’t just about “men’s jobs”. It was about dismantling the structures that left generations of women invisible and exploited.

Caught between the crucifix and the Queen.

What Are the MacBride Principles?

Named after Seán MacBride – Nobel Peace Prize winner, freedom fighter, and general thorn in the side of empire – these principles were a simple set of fair employment guidelines.

They said things like:

- Don’t discriminate.

- Advertise jobs publicly.

- Make promotion and hiring transparent.

- Set up oversight and training to ensure fairness.

Radical stuff, right? Well, only if you’ve been trying to preserve a centuries-old system of economic apartheid.

These weren’t empty slogans. They were legally binding standards that companies had to follow if they wanted a slice of investment from states like New York or California—where Irish America was thick on the ground and politically potent.

By the mid-1990s, over 40 US states and cities had adopted the MacBride Principles.

Corporations doing business in Northern Ireland suddenly found themselves accountable – not to London, but to their shareholders and boardrooms in Chicago, San Francisco, and Albany.

Martin Galvin, Noraid & the Politics of Pressure

No conversation about Irish-American influence is complete without Martin Galvin. Bronx-born, firebrand lawyer, and unapologetic spokesperson for Noraid – the Irish Northern Aid Committee.

Yes, Noraid had its controversies. It was accused of funding the IRA (and depending on who you ask, proudly so). But it was also a powerful organising force. Galvin used his legal chops and political connections not just to fundraise, but to lobby, educate, and agitate.

He had one message for America: if your tax dollars are propping up British injustice, you’re complicit.

Noraid turned Irish bars and community halls into political education centres. They were loud, relentless, and impossible to ignore. And when the mainstream Irish-American establishment- think senators like Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Ted Kennedy – finally caught on, they brought the full weight of US soft power to bear.

Wall Street vs. Westminster

The genius of the MacBride campaign was its simplicity: make economic injustice too expensive to ignore.

Multinationals – General Motors, Ford, IBM – found themselves facing awkward questions from investors.

“Are you complicit in discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland?” Their legal departments began twitching. Their PR departments broke into sweats.

Britain could ignore protests. It could dismiss riots as ‘terrorism.’ But it couldn’t ignore Wall Street. And when America started asking hard questions about human rights in the six counties, the empire had to listen.

A Quiet Revolution in Hiring Policies

By the late ‘90s, the MacBride Principles had become more than just guidelines.

They were embedded into the Good Friday Agreement’s spirit of equality. Fair employment monitoring became standard. Discrimination still existed, of course, but now it had consequences.

In a poetic twist, the same Ireland that had been exported as a problem—colonised, stereotyped, starved, and scattered – returned a solution. The diaspora brought justice not with guns, but with pensions and procurement policies.

Nice Work, Ladies

But let’s circle back to the women. The ones who weren’t on the posters or the podiums, but who kept the entire show on the road.

It was Catholic mothers who raised their kids while dodging army patrols, who showed up to clean offices they were never allowed to manage, who made ends meet on half a wage and a rosary.

It was Catholic daughters who went to schools with fewer resources, and still dared to demand more. And it was Irish-American women – nurses, nuns, unionists, and secretaries – who helped push the MacBride campaign through town halls and state legislatures with a fury that could melt marble.

So yes, the MacBride Principles were about jobs. But they were also about visibility, dignity, and the unsexy power of policy.

They said: we see you. We know what’s happening. And we won’t let it slide anymore.

And Why It Still Matters

Because the fight for justice is never just about one thing. The domestic is political. Your job, your pay, your postcode – none of it exists in a vacuum.

This story matters because it shows us that you don’t need to be in the room to change the terms of the debate. You just need to be loud enough, organised enough, and relentless enough to force the door open.

Irish America knew that. They didn’t wait for permission. They made their own rules.

Leave a comment