And how we’re quietly getting ourselves back…

Colonisation in Ireland wasn’t a chapter. It’s been pretty much the whole story.

Eight hundred years of it. Land stolen, language banned, minds bent to fit the master’s mould.

When the South finally broke free a century ago, people thought the job was done.

But as James Connolly warned,

“If you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the Socialist Republic, your efforts would be in vain.”

He was right.

The empire left the building, but its systems stayed on. Repainted, rebranded and still collecting rent.

The uniforms changed; the logic didn’t.

The North stayed under the Crown. The South stayed under the spell.

And both halves kept blaming each other while the same old game rolled on.

That’s the real trick of colonisation: teaching the oppressed to police themselves.

To fight each other instead of the structure.

To see hierarchy as heritage, and hardship as normal.

Here’s how they did it, and how Irish people are quietly undoing it…

Religion

They weren’t just building churches. They were planting division and boundaries.

Around here, judgement day is every day.

Church and state moved together for centuries, teaching guilt, shame and who to blame. That is what scholars like Eve Tuck call internalised occupation. Control moves from outside to inside, so people end up policing themselves.

What is changing now is the hold, not just the label. In the North’s 2021 census, Christian identity is still the majority, but the fastest growth is among people with no religion. That’s up to 19 percent. Protestant identification has fallen long term from two thirds of the population to just over a third, while Catholic identification has grown to around two fifths. The direction is steady: religious power is loosening.

Across the island you can see the same pattern. In the Republic’s 2022 census, Catholic identity fell to 69 percent and the share reporting no religion rose to 14 percent. Scotland’s most recent census found a majority with no religion for the first time. These are not blips. They show a wider shift away from institutional religion.

Here is the important bit for ordinary life in the North: As the grip of organised religion eases, more people are quietly rejecting sectarian habits. You can see it in the choices parents make and in the projects that bring kids together.

• Sport is doing quiet, serious work. PeacePlayers brings young people from both traditions into sustained contact. Independent evaluations report large jumps in cross-community friendships and confidence to challenge prejudice after taking part.

• Shared spaces are becoming normal. The Skainos project in East Belfast is a good example of a permanent, open, cross-community hub delivering services and daily contact, rooted in a former single-identity area. skainos.org+2nicva.org+2

• There is an annual showcase of this work. Good Relations Week now runs hundreds of free events in all 11 council areas, highlighting projects that tackle sectarianism and build everyday connections. This is people power in public view.

What does all that add up to? A quiet reset. Ordinary decent people are choosing decency over division. Faith is moving from dogma to everyday ethics. No middlemen required.

Education

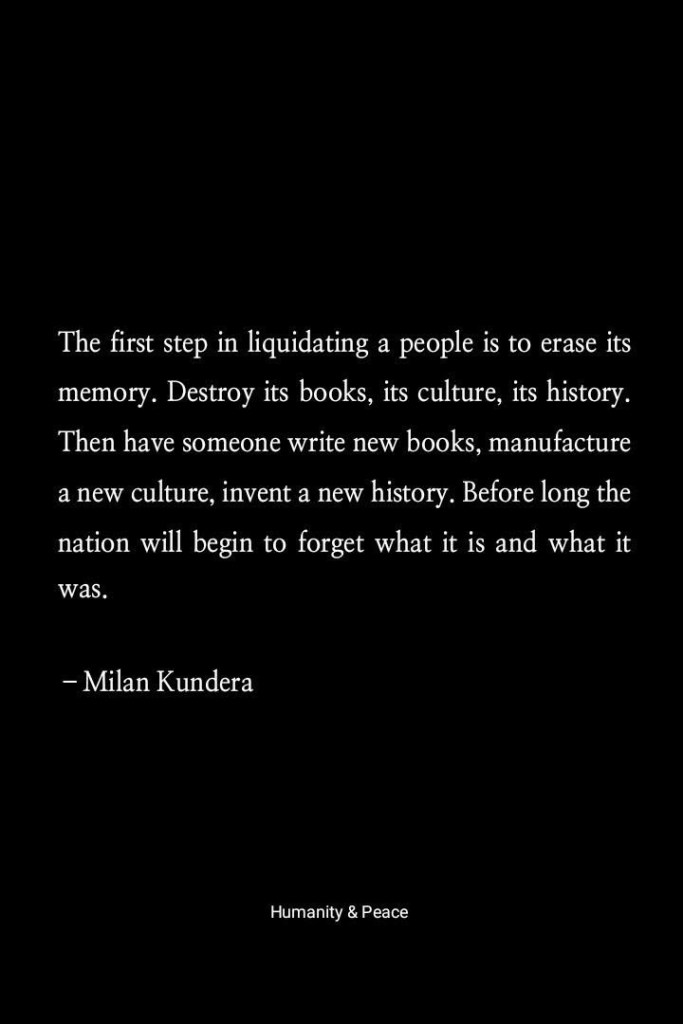

Then they wrote the script.

British rule didn’t just take power; it defined what “knowledge” meant.

The schoolroom became the engine room.

As Linda Tuhiwai Smith wrote in Decolonizing Methodologies, colonial schooling “taught people to see themselves through someone else’s eyes.”

We learnt about English kings from British poets.

We left school fluent in someone else’s story – but not our own.

That’s starting to shift.

Irish teachers and parents are rewriting the script, bringing back the local, the oral, the lived.

• Integrated education is growing. In 2024–25 there were 71 integrated schools and about eight and a half percent of pupils attending an integrated primary or post-primary. That is still modest, but it is the highest yet and rising. The research record shows integrated and shared models help build positive relationships across the old divide.

• Shared education keeps expanding. Department programmes and EU PEACE funding have backed joint classes and projects between Catholic and Protestant schools, with evaluations showing improved attitudes and skills for living well together.

As Smith would say, this is knowledge as healing – truth as reclamation.

Language

Maybe the cruellest trick of all.

They didn’t just take the land. They took the words.

Out of the mouths of babes, literally.

Schools beat it out. Churches shamed it out.

Parents stopped passing it down so their children could “get on.”

And that silence did what occupation always does: it broke connection.

Children couldn’t speak to their own parents. Communities couldn’t speak in their own rhythm.

That’s what colonisation does best: it gets between people at the most intimate level in the most insidious way.

But here’s the gorgeous twist: the words are coming back.

Irish is rising again. On TikTok, in hip-hop, in memes, in murals.

Not as nostalgia, but as repair.

As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o said, language is the “collective memory bank of a people’s experience.”

When we speak our own tongue, we’re cashing back in.

Politics

Divide and conquer. Northern edition. Two flags. One endless row. That is the structure, not a phase.

Tuck and Yang’s point stands: colonisation is a living system that keeps reproducing itself through what we call ‘normal’.

Who ultimately writes the rules? Westminster does.

It’s the constitution. The Northern Ireland Act 1998 embeds the consent principle, yet UK parliamentary sovereignty remains the supreme legal authority. Courts have reaffirmed it in recent protocol challenges.

Translation: Stormont can govern, but Westminster can make or unmake law.

So are Sinn Féin just playing the game with the master’s tools? You can argue Audre Lorde’s line all day, but there is movement you can point to without romanticising it.

Receipts for movement

- First nationalist First Minister and outreach across old lines

Sinn Féin became the largest party at Stormont in May 2022 and gained the right to nominate the First Minister. Michelle O’Neill later took office and, in November 2024 and 2025, attended Belfast’s Remembrance ceremony, the first senior Sinn Féin figure to do so. That is symbolic politics with real audiences, not just performance. - Hat-trick across elections

Since 2022 the pattern has held. Largest at the Assembly in 2022. Largest at councils in 2023. Largest Westminster party from Northern Ireland in 2024. This is not noise. It is a voter trend. - The centre ground is real and growing in influence

Alliance finished third in 2022 with its best ever vote share, and in 2024 took Lagan Valley, a symbolic seat in unionist politics. That reflects a public appetite for less tribe, more problem solving. - Identities are more fluid than the flags suggest

The Northern Ireland Life and Times series shows long-run growth of people who call themselves neither unionist nor nationalist, peaking in 2018 and settling lower since, but still a major bloc. This is the electorate that punishes performative rows and rewards delivery.

Call it what it is.

Yes, politics is only one strand and London still holds the legal pen. But the field is shifting.

Voters have handed Sinn Féin the top spot in three contests in a row.

Alliance keeps making inroads, and the share of people who reject the old labels has been large enough to shape results for years.

That does not end the structure, but it changes the incentives within it. Parties that keep to old scripts are punished. Parties that cross old lines, even awkwardly, are rewarded. That is movement. Not victory, not purity, but real.

Economics

They didn’t just take the land. They built a system to keep taking.

Colonial economics never left; it just switched accent.

The old landlords became property developers, the empire became the market and the rent still leaves the country.

Ireland’s housing, energy, and retail sectors remain dominated by multinationals. Profits flow out faster than they circulate in. The Central Bank estimated over €100 billion left the state through profit repatriation in 2023 alone.

This is what post-colonial scholars call extractive continuity, when the flag changes, but the flow of wealth stays one-way.

Capitalism runs the same play. It mines time, labour, and land, calling exhaustion “growth.”

The system is still extractive at its core. The only question is whether we’re learning to tame it.

And maybe, slowly, we are.

Co-ops, credit unions, circular economies, local food networks. Small acts of economic independence are building a quieter republic of enough.

Not revolution. Evolution.

Rooted wealth instead of endless extraction.

Sexism

The coloniser didn’t just run empire. He ran households too.

Taught men to rule and women to serve.

From Magdalene laundries to the marriage bar, the control was total.

But as feminist scholars have long pointed out, patriarchy was both a weapon and a model of empire: you dominate the home the same way you dominate a colony.

That’s why decolonisation has to be feminist – it’s the same fight.

And women are leading the repair – not with revenge, but with balance.

Fairness is the new frontier.

The Quiet Revolution

This isn’t about revenge. It’s about repair

As Tuck and Yang remind us, real decolonisation isn’t a metaphor. It’s material.

It’s about land, language, labour, and love.

But it doesn’t have to be loud.

It’s in the shop that buys local.

The teacher who slips Irish words into science class.

The fella who stops saying “that’s just the way it is” and starts saying “there’s something wrong with this picture”.

It’s people taking back what was always theirs: their time, their tongue, their truth.

And that’s the part they never planned for.

This is how they have us.

And this is how we’re getting free.

Leave a comment